Describe your Ethnic Background: the long story

London, 2021

Sometime back I was sitting at a long white oval table in a seminar room with two professors. A question arose. A certain air of consternation hovered about the question like a monsoon storm cloud about to burst. I was being asked: ‘what are your politics?’ Where did I stand on issues of race, gender and class? The second question was only implied, but I know that what I was actually being asked about were my allegiances, or more bluntly, my identity.

I was under scrutiny, an attempt at capture. I felt myself beginning to heat up, the sweat of panic seeping from my pores. My squirming countenance might leak out the reality concealed beyond my endless attempts at camouflage. But what is that reality, what lies in the sub-cutaneous realm of my politics, of my allegiances, of my identity?

The charge of the storm cloud, although invisible, was latent. The silent concern surrounded my research title The Space of the Nameless. For an academic doctoral project, it was too ‘open’, too naïve perhaps, worryingly unaware of theories of difference; of critical race theory, of feminist theory, of post-colonial theory, thus not intellectual enough, not critical enough, too blindly optimistic. Was I imagining a world without the need for names, labels, categories? Was I entertaining the illusion of a flaccid, homogenous unity by calling for namelessness?

Who am I?

If my politics are my power — my agency in society, which emanates from my identity — before speaking of my politics, I’d need to know who I am. But this is a question that reveals patterns of concentric circles, like the rings of a tree, the onion-skin logic of the Russian doll: it deepens and expands in time and across successive levels of materiality, there is no quick answer to give, no easy box to be ticked.

The external layer of my body-material changes with the weather. The pigmentation of my epidermis moves across a gradient, from light brown in places where the winter is cold and sunless, to darker shades when the sun is about. For reference and a recognizable categorization, these browns are equivalent to a gradient between 4655C and 4635C on the Pantone Solid Colour scale.

While the surface of my body tends towards my father’s heritage, oddly and frustratingly I inherited my Mum’s complexion on only one single body part: my face is the palest patch, with cheeks that go pink in cold weather or flush bright red when I do any kind of exercise…and oh, how I dislike having a face that says too much about my inner state. Something must have gone wrong in mixing up the colour palette of my body-material, because I’m also lighter than all my siblings, with brown hair instead of black and green-brown eyes instead of dark brown.

Who, or rather what am I?

I am what’s known as ‘biracial’ — and probably more than just ‘bi’ if the question was propelled further back in time. My mother is French, but also a quarter Sicilian, and by all accounts the island of Sicily, in its suspension between continents and ethnic groups, would reveal a much more ‘multi’ stranded ethnicity on her side. My father is Indian, but again his blue eyes reveal that ethnic multitudes lurk in his ancestry too.

With my rosy cheeks, I easily pass for white. Unless someone knows me personally or asks me questions about my family background, most people assume I am white, though more Southern European or Mediterranean than Anglo-Saxon. My professors, like most, addressed me from that assumption, but also knew there was more to uncover. Remembering the actual exchange, I had mentioned that I’d lived in Zimbabwe for part of my youth. I recall something along the lines of someone saying, and I’m totally paraphrasing: ‘because you look white, you must have been accepted by, and therefore mixed with, white people’ and subsequently, that would be the group with whom I would identify. Was she really making such a simple assumption? I wondered how much time we had left of our meeting. Although I tried my best to explain, a short hour was just not enough to guide my professors along the meandering scenic route that leads to the viewing platform, and the vast horizon of my identity.

How do you pack up a horizon into a carrier bag? By twisting so many unruly strands I’ve tried time and again to stuff the horizon into a portable container identity, in order to make friends, in order to belong, in order to get recognition, in order to fit in, in order to simplify things, in order to cut a long story short. But here, now, I want to walk along the scenic route.

I know, the bagged up, (tick) boxed-up identity, is there to make me palatable, acceptable, and through this I earn social visibility, I may join the conversation because now I can enter the social through the group’s language, I have the right to speak, in exchange for making myself recognizable, identifiable. But I also know that to box up my identity is also to congeal its flux, its responsiveness, its porosity, to others, and to the elements, the sun, the wind, the ice. In the box, in the bag, I am captured. But there is in me, has always been, a subtle resistance to the capturing device that is identity: I prefer to shape-shift. My act of resistance has always been to dissimulate myself into the background, through manifold methods of camouflage: complexion, accent, voice, language, clothing, gestures, cultural activities, food. These adaptive behaviours are not so much a desire to fit in, but rather a means to listen to my surroundings, to tap in, to hear the secrets of each identity group. The range of my disguises always made me feel I was a spy.

My research project, The Space of the Nameless, was to be a form of code-breaking manual that might reveal these methods and tactics by unravelling the unfathomable existence of a fluid logic of identity. It would almost be like declassifying top secret files.

Who am I is also to ask, where am I from?

My father is Indian, born at the threshold of the Himalayas, in the hill station of Mussoorie, a small town that is also a favourite honeymoon destination for Indian newlyweds. Dad grew up in colonial India and had an English boarding school education in one of the Doon schools. He, his siblings and his close ancestors, parents, grandparents, bear the traces of colonization through their urge to become Anglicized as a means to gain the respect of their colonial rulers. Our family tree, stretches back over a millennium of generations, revealing that the name Bonarjee is in fact a slow reformulation over time of the original Bhattanarayana line of Kulin Brahmins that settled in Calcutta around 1065 CE. This cartography of ancestors reveals a family clan of politicians, lawyers and holy men…And no doubt women, although following the patriarchal order, the women never made it onto the family tree.

Woomesh Chunder Bonnerjee (1844-1906) is still remembered as the famous Bengali politician who led the Indian National Congress as its first president, preceding Mahatma Gandhi. I say ‘still’ because I experienced his legacy first hand when I was at the Indian High Commission some years ago. While I was waiting in a crowded room to get my Indian visa, the person sitting next to me, glanced at my passport, and happened to notice my name. ‘Are you related to WC Bonnerjee?’ he asked somewhat incredulously. When I nodded, he was bowled over with enthusiastic glee, assuring me that he would tell everyone he knew that he’d met a relative of Bengal’s ‘most famous politician’.

My great uncle Neil Bonarjee worked for the Indian Civil Service (ICS) under the British Raj. He wrote a book about the inner split he experienced. The cover of Under Two Masters depicts the British and Indian flags crossing over each other: perhaps at their crossover point, the ‘x’ marks the spot where he hoped to anchor his own identity. Neil’s older sister, my great aunt, Dorothy Noël (1894-1983), was one of the first ‘brown women’ accepted at Oxford University. But instead of ‘graciously’ accepting her invitation to join the English elite, she turned down the offer. Seeing herself as a poet and convinced that England wasn’t the place for her to deploy her poetry, she opted to go to Wales instead. There, at Aberystwyth University, she was elected the first woman and first Indian to hold the Bardic chair of poetry.

When she graduated, having been educated alongside her brothers in a way few other Indian women had, it was expected that she’d use her privilege proactively by entering the ICS and help shape Indian society under the Raj. But she, the poetess, refused, and again escaped her fate, this time disappearing from the scene when her father, Debendra Nath was at sea on his way from India, ready to take her back with him. By the time Debendra Nath arrived in London, she was gone, and he, his pride wounded, publicly disowned her in The Times newspaper.

She had eloped with a French artist, Paul Surtel, and moved to Provence to continue her artistic life as a painter and writer. She went on to be active in the Resistance movement in France, secretly smuggling Jewish children out of Marseille, using the documents of her young son, who had died in infancy. My aunt, Sheela, loves recounting how great aunt ‘Dorf’ had such a powerful and audacious charm that even when the Nazi soldiers would come to her door, suspecting her activities, she would regale them, thus throwing them off guard with tales of her own true Aryan ancestry.

My grandfather, Bertie Kay Bonarjee, was a ‘dilettante’ as I’ve been told. I never knew him. During the three siblings’ education, he had been his sister’s guardian, and had to accompany her to Aberystwyth University, whether he liked it or not. Apparently, she was the more brilliant of the siblings and she got to choose. Good for her, she was an early feminist, before the name ‘feminist’ even existed to describe her identity. Bertie was first ordered to accompany his sister, he did. Then, again, he followed his father’s orders returning to India for a late arranged marriage: an unhappy one. But he, like his sister, broke rank by not entering the ICS. Educated as a barrister, he spent his life researching Indo-European languages.

I received a copy of his old notebooks. I leafed through the pages, wanting to know him, wanting to understand where he belongs? Under which discipline, which allegiance, which ‘master’? They called him a ‘dilettante’ because he moved between places, between interests, leaving his belongings scattered in forgotten suitcases. He was fluid, his passions moved him, he belonged nowhere. But still, he wanted to, or maybe he hoped that he might arrive somewhere, and put an end to his perpetual unhomeliness. A name can do that right? But he took it literally, rather than naming his identity, he changed his name. He translated the family title, zamindar, to Baron. By doing this, he thought he might earn the respect he craved, the respect that comes with belonging. Instead he’s remembered as the ‘crazy old man’ by his wife, my gran, or just the dilettante, the amateur.

And he was an ‘amateur’ in the true sense, because he loved. He loved discovering connections between diverse cultures across time, and he learned Greek and Latin because he loved unpicking culture by undoing language at the seams. He did this through comparative studies of ancient Sanskrit which he learned from the Sadhus in their saffron robes, whom he used to entertain in the family home (to his wife’s horror), offering them ‘the classics’ in exchange for their knowledge. He also loved collecting coins, as if wanting to learn how the logic of fluidity which he knew so well (yet I doubt he knew that he knew it) materializes as hard currency. He also loved music and song and played the popular tunes of his times on the piano: my aunt still sings them off by heart. He spent a lifetime trying to order things, to classify his hidden wealth of knowledge by making lists. Lists as devices that might allow him to time travel to the ancient past, to the civilization he wanted to belong to.

Each list begins with the Sanskrit word, and then, in a neat handwriting, he follows its declension over time, into Persian, Hindi, Zend, Pali, Latin, Greek, Slavic, Germanic, Teutonic, Gaelic, Celtic, Scotch and, English. The lists are grouped under a number of categories: Relationships, Mythology, Anatomy, Animals, Life Mind Death etc., Geography, Artificial Objects, Eat Drink Food, Time and Seasons, Flora, Metals. Each list is a ladder that let his inquisitive mind escape through others’ names. Things that are named ‘cuttlefish’, or ‘foam’, or ‘entrails’, or ’wing’ or ’sea’ gave him passage to the depths, to the oceans of time, where he might land, and rest at last, by finding solace in the deep benthos of the lost. He was looking for his name, a name that existed before he or his parents or his ancestors did. Was he looking for home, or for his own dissolution?

Even changing the family name did not protect the next generation, my father and his siblings, from institutional and societal racism. My father, Hector, and his late brother, Theodore, were chased and assaulted in London, by Teddy boys with knives, an incident that still rings through Dad’s memory. His sister, Sheela, experienced prejudice in the college where she taught, when parents didn’t want their children to be taught by ‘an Indian lady who probably didn’t speak very good English’. On another occasion my aunt who ran an employment agency at one time, managed to terrify a white South African girl who was looking for a job in London. When the girl entered Sheela’s office, she thought my aunt must be the cleaner or some lowly helper. When she realised that she was in fact the boss, the girl ran out, shrieking ‘she’s a kaffer’[1] all the way down the stairs.

My uncle died too young; nobody seems to know the cause of death. They simply say ‘he died of a broken heart’. What they do know is that a short time before this tragedy he had tried to meet with his three young children after they had been taken away to Leeds by their mother who was having an affair with the local handyman. When my uncle arrived in Leeds, outside his wife’s family’s house, wanting to see his young children, he was met by his estranged wife’s brothers who threatened to beat him up if he didn’t go away. He died alone and never saw his children again.

My French mother, Lucette, was born in Paris into a working-class family. Her father, Charles, was a taxi driver and a trade union leader. I feared him, the memory I have of him is of a hard, strict and unpredictable man. My mum left the family home when she was still young, wanting to become independent. Through her secretarial job at the Sorbonne, she could afford to go on holidays by herself. And so it happened that she met the love of her life while backpacking in Italy. He, my dad, then moved to Paris, and one day, waking up from a prophetic dream, he suggested that they leave for India. And they did, hitch-hiking across Europe and then Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan to arrive back in Mussoorie where they got married.

This is the ‘fairytale romance’ as my Dad still calls it, having retold the story of their early love in a book under that title. When the two of them set off from Porte d’Italie, Lucette was about to embark on a life that would be very different from anyone else in her family. To the French bourgeois relatives who stayed put in the homeland, she is aunty ‘baba-cool’, and she loves that.

When I started school in Jersey, I didn’t speak much English. My mother-tongue is French, and we’d only spoken French at home. Apart from my weird accent and slower access to vocabulary, I was also darker than the other kids in school, and horror of horrors I wore a couple of strange items of clothing. In the winter, my Mum made me wear a printed Indian silk scarf underneath my school uniform, believing it would protect me from getting colds. She also refused to let me wear school regulation underwear, because it was not ‘one hundred percent cotton’. Whenever anyone saw my knickers when I was on the jungle gym, I was teased and singled out… a kid’s life. But to top it all I had this long-winded name and surname that nobody could be bothered to pronounce. My Dad had taken back the Bonarjee name, dropped by his father, to form a double-barreled mouthful: the Baron-Bonarjees. The weird accent, the weird scarf, the weird name, all made me stick out as different and making friends was incredibly tough. I so longed to just be called Jane or Emma or Anne to make things easier.

Later we moved to Zimbabwe (we’d already moved quite a bit before that, but I leave this out for brevity). Dad was tired of Europe, especially the weather, that’s what he says, and then he’d quickly add, to spice his cause up with contemporary relevance, that ‘he didn’t want us to grow up in a monoculture’. And the final reason for our very sudden move, is that he was ‘tired of looking down the mouths of rich people’ – he’s a dentist – and he wanted to use his profession to help people who really needed him. These are the official reasons, I think there are unspoken ones too, but who knows if I’ll ever hear those.

In the first school I attended in Harare, I was one of the only ‘lighter-skinned’ girls in my year, a total reversal of my experience in Jersey. It soon became apparent that here, race and colour was an issue that had to be negotiated on a daily basis. ‘White’ people in Zimbabwe were mostly what was colloquially referred to as ‘rhodies’: they thought or pretended, that they were still living in Rhodesia and tended to behave that way too. They were the ‘when we’s’ forever making judgements and comparisons between the post-independence politics, and the ‘golden era’ that preceded it: ‘when we were in power, things were better, more efficient, ran smoothly, etc’. They were mostly arrogant, racist, and their culture was rooted in meat-eating and heavy-drinking.

My mother was not happy in Zimbabwe. She might bear the ruddy white skin of a Caucasian redhead, but these were not her people. But the automatic identification of fair-skinned people with rhodies worked against her and that must have really infuriated her. She was Parisian for God’s sake! She’d spent her whole youth, strategizing her independence, and then working hard towards achieving style and sophistication, and now she was being identified with a culture of boozing and barbecues. She must have really resented this misidentification, and I’m almost sure her French accent intensified after we moved there.

When Robert Mugabe came to power after Zimbabwe’s Independence, his policy was one of openness, not wanting to drive away other races. Still, many wanted to get their revenge for what they’d suffered under colonialism, Ian Smith’s regime and the long War of Liberation (the Second Chimurenga War, 1964-1979). People were encouraged to report racist slurs, and what is now called ‘hate-speech’, to the police. One of the worst insults was to call someone a ‘kaffer’ – a particular Southern African racist slur as I mentioned earlier. One day my Mum was at a bakery, with her strong French accent, she asked for something, a bakery item obviously. There was a queue of people, perhaps the atmosphere was a bit tense because people had been waiting, perhaps my Mum’s tone was a little bit exasperated because of the heat: I’m just surmising because I was waiting for her outside. Suddenly the woman behind the counter shouted out to the other customers, “she called me kaffer!”. How on earth would a Southern African slur roll off my French Mum’s tongue in the middle of a packed shop, where she was the only ‘white’ person?

I can’t be sure, but I have a feeling that it was after this incident that my mother became very unhappy. That outrageous public accusation, where she felt that everyone had turned against her because of her race, must have carved a deep groove in her memory, and her heart. Was it because of this humiliation that she became fearful, and to protect herself she shut herself off, she turned hard, just like her father had. Our friends used to jokingly call her the Iron Maiden but they were genuinely scared of her.

My two brothers attended an all boys’ school that still dished out corporal punishment and other sadistic practices. In the boys’ school, the unofficial segregation was intense. The black Zimbabwean boys were obviously the largest group, they seemed less contained by specific in-group signifiers. The subgroups were the white rhodie kids who would all stick together wearing long knee-high socks, playing rugby and driving pickup trucks – I’m making generalisations but that was the overarching flavor of the group. There were the ‘coloureds’—a completely politically incorrect term now, but in Zimbabwe mixed race people, perhaps still unknowingly echoing their previous colonial rulers, referred to themselves as ‘coloureds’, and they still do. They also had their own way of speaking, their own accent, their own slang, and they mostly drove hatchbacks. The smaller minorities were the Indians and Moslems, whose fathers were all businessmen, and they also stuck together driving fast expensive cars with loud sound systems. Then there were the Mediterranean communities of Italians, Greeks and Jews, who also tended to stick together. And finally there were the stray expats from the various embassies, who came sporadically and would leave just as suddenly when their parents took up a new post. My brothers didn’t fall into any of these groups, but moved amongst many if not all of them, mostly getting taken for diplomat’s children because we spoke French.

Sometimes we mixed with the tightknit Indian community, and sometimes with the embassy people, enjoying receptions in their luxurious villas. But my Dad’s place of work was anything but leafy and luxurious. He worked in one of the highest density areas of Harare known as the ‘cow’s guts’. It was a place where most people (the lighter ones especially) feared to tread. Dad had left the Channel Islands and its millionaires (and billionaires), wanting to make himself useful to people who needed him, as he claimed. In Zimbabwe he offered his services to the poorest people, and they would come in droves to his surgery in this dusty part of town.

When my friends remember the pop songs of their youth, I realise pop culture didn’t exist for me after we left Europe. Consumer culture was much patchier in Zimbabwe, no Top of the Pops, no HMV, no high street fashion shops, no Radio 1 DJs. If we wanted access to pop, it was achieved with great effort — copying tapes and CDs from friends who had been ‘overseas’ — and at times, some black-market dabbling too. The music I remember most fondly is Chimurenga. I loved this revolutionary deep song of Zimbabwe’s struggle for independence, sung by the likes of Thomas Mapfumo and Oliver Mtukudzi. My Dad would put it on the record player and all of us would sing along, even though we didn’t understand any of the words, and we’d dance around the living room together, sometimes teary eyed, fueled by a secret emotional charge that moved amongst us, unspoken.

Whether we liked it or not, we were made to follow in the wake of my Dad’s humanitarian and multicultural ambitions. Nevertheless, all of us inhabited a confused world of categories of skin colour, of coded insults, of in-groups and out-groups, hatchbacks and pickup trucks, and we just slipped between the cracks of all these factions. Though not one of us, to this day, has spoken about our experiences in that climate. Was the unspoken fear that if we did, it would bring up the whole issue of race and culture to the table? In our family it was almost taboo. My parents would never have called us ‘mixed race’. My Mum was in fact outraged by the forms that the schools required her to complete asking what racial category we fell into. She refused to fill them in, she would not tick white or coloured or Asian. Perhaps my parents suspected we might experience prejudice because of their determination in going beyond the confines of their own cultures. And they were definitely aware of the undercurrent of unease we faced in societies that insist upon such identifications. One evening at dinner my Dad, who loved to read news stories or history books to us at the end of the meal, pulled out an international newspaper and quoted directly from an article he had just read: “if anybody asks you where you’re from, tell them you’re a ‘citizen of the world’!” he advised us with a triumphant flourish. He was delighted, he’d found the expression he needed to liberate us from the torments of identity… or so he thought.

That dinner table slowly emptied over the years, as each of us went our own ways in the world. And still, we never really talked about all this with each other.

For a short period at the end of our teens, my brother, Xavier, and I were living together in Cape Town, South Africa. He was going through something of an inner crisis, which manifested in manic behaviour accompanied by bouts of magical-realist storytelling. He would indulge in this fantasizing with anyone who cared to listen to him. He’d found a photograph somewhere, possibly on the street or in a market, I’m not sure. It was of an old African couple, man and woman. He pasted it onto the inside of his bedroom cupboard, and whenever anyone visited us, he would start recounting ‘his story’ to them, always in a low conspiratorial tone, as if he didn’t want me to hear. The secret tale was that this old couple were in fact his real parents. The story went that he was originally born in a village in the rural Congo, and he was the son of a village chief. Their village had been attacked when he was a very young child and he had been abandoned as everyone had been killed or kidnapped. Now orphaned, another couple, my parents, had adopted him because of the language and colonial connection to France: as he spoke French, the adoption agency had thought this would be a good match. To demonstrate his Congolese heritage, he had a shirt especially embroidered with the name ‘Kinshasa FC’ to honour his alleged homeland’s football club.

Hearing this story, his confidantes became perplexed. They could see a resemblance between the two of us, but more than just that, despite being darker than me, he didn’t look very racially black. But Xavier, who has a gift for spouting spontaneous nonsense — and sometimes sense – would have an answer ready for them. He had been very young when he was adopted, and so he had grown up to start looking like his adopted family. He would add that this phenomenon has been observed in couples who start to resemble each other, or even pets, especially dogs, who can start looking like their owners. He added that he was a lighter-skinned Congolese child anyway, and whether it was his persuasive tones, or some form of hypnotism at work – he is quite a charismatic character — many of his friends, and even mine, began to believe him. They would approach me to confirm it all: “So Xavier was originally adopted in the Congo?” The intonation didn’t express any kind of doubt, but instead it was tinged with a certain awe: how did I feel having an adopted brother from Congolese tribal royalty?

Whereas Xavier had opted for outrageous fabulation, I just shape-shifted through the affordances of my varying skin tones, without saying too much about myself, knowing the prejudice I might encounter in this racially-obsessed society.

In Cape Town, there is quite a large Jewish presence, and I was often taken for an Israeli, because of my complexion and curly hair. I noted these mis-categorizations with a certain glee, the sense that ‘I have them fooled’ gave me that secret power, that of the undercover spy excelling at her mission. But one day the ‘mission’ was brutally exposed.

I was at a small gathering, invited by a school friend who was herself Jewish. A Jewish boy who had been pursuing me, but in who I had little interest, approached me outside.

‘Someone told me you have an Indian father, you didn’t tell us this, is it true?’

I could feel the blood rushing to my head. The ‘someone’ who’d disclosed this, was a Greek girl who I’d been at school with in Zimbabwe, although she was in a different year group. I presume she’d seen my Dad at the school gates, but didn’t know him, and she didn’t really know me either.

‘Yes’ I replied in a small barely audible voice, all my undercover powers fizzling out.

I can’t recall exactly what his words were, but he more or less threatened me, saying that he would ‘reveal’ my identity to everyone else, and then they’d know that I was pretending to be something I’m not, and that I wasn’t one of them.

I can still feel the mute fury, the creeping sense of being ashamed of something and I didn’t even know what. I couldn’t help it, or change it: what would the others think of me if he told them — whatever it was he was ‘accusing’ me of? My thoughts were irrational, I didn’t even stop to consider the immature stupidity of this boy, and what amounted to racial blackmail.

But from that moment on, I realized that we’d never be black enough, or white enough or brown enough, or olive enough to be part of any of the many ‘cliques’ that persist long after apartheid has been dismantled. But it’s not just in South Africa that I’m talking about, the same logic of ‘cliques’ unravels itself under different guises, everywhere: identifying, grouping, naming, belonging, including, excluding, marking, categorizing, classing, narrativizing, dogmatizing, separating, exposing, dividing, ruling.

My parents had to move back to Europe after the inflation crisis in Zimbabwe in the late 90s, when they lost both their pensions and savings. They have now grudgingly come to terms with a less colourful life in France. My mother is the one who now teaches Yoga and preaches vegetarianism to everybody she knows. My father, still a dreamer, who loves to recall being taken home on an elephant when he would return from boarding school for the holidays, is often taken for a refugee, or a North African immigrant. To their dismay, most of their neighbours voted for Marine Le Pen’s party in the last election. My Dad vows to leave if she were ever to be elected. My Mum complains about French arrogance and entitlement. They don’t belong, they are not at home, there, or anywhere.

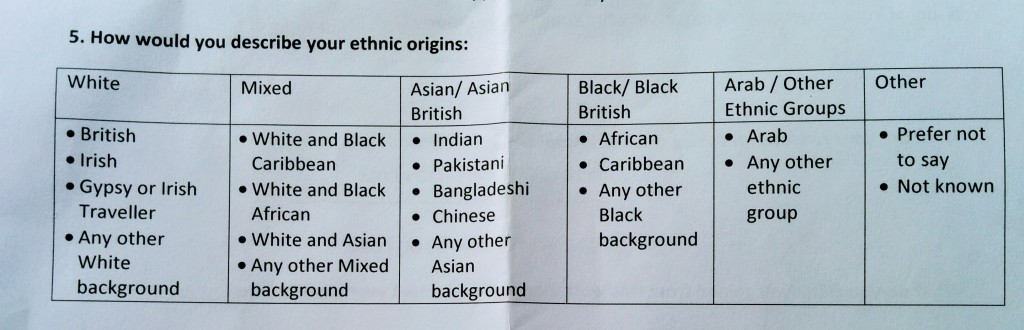

To cut this long meander short, I hope you, the institutions, the academies, the subcultures, the identity groups, will understand why I am still resistant and still insulted when I have to squeeze myself into a check box for ‘equal opportunities’ forms that ask me to identify with a category, a colour, or a strange blend of monochrome and ethnicity described as ‘white and Asian’. The mark I make will be used, I know, to capture my data and to eventually ‘prove’ or ‘justify’ that ‘things are changing’, that others are getting access to the cultural, political and social spaces, previously closed-off to them. Perhaps it’s even true. But ticking the ‘other’ box will never do justice to the endlessly expanding horizon of each person’s identity, which I might as well just call, ‘the nameless space that allows for the fluid movement of being.’

LINKS:

Dorothy N. Bonarjee: ‘She is beautiful but she is Indian’: The student who became a Welsh bard at 19

Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee: Biography

[1] The ‘kaffer’ insult comes from ‘kaffir’ which in Islam indicates a nonbeliever: in Southern Africa it had become bastardised into a racist slur.